Henry Sprite and Simon Denny

Issue 01 introduces Henry Sprite, an artist and creative director behind the infamous Milady Maker NFT collection, in conversation with acclaimed artist Simon Denny.

The two artists speak on anime, NFTs and Warhol ahead of Henry's upcoming Sentimental Graffiti, Drop 11 on Zien. This is Issue 01 of the revived Art of Conversation format, chronicling periodical conversations between todays foremost artists and their chosen interlocutor. Published by Zien, a Web3 platform for digital-physical contemporary art.

Henry

Since the last time I talked to you the main thing that's happened is I got one of the vitrines installed as a table.

Simon

Can I see it?

Henry

Yeah, I can show it to you. This is the first time I've seen it. I'm still waiting on the panel at the top that was supposed to come this morning. It will all be done soon.

Simon

How does it feel in the room?

Henry

It feels good. It feels like the correct scale. It's funny to me going from a digital thing that you're mostly looking at on your phone to this thing that's occupying my living room.

Simon

Do you want to talk about your journey and how you started making NFTs and also art in general?

Henry

Art and also design were always things that I was interested in. I started studying industrial design in Wellington. But it's definitely more a story of stumbling into it than starting out with an intention. I'm kind of happy about that because I think what I ended up really enjoying were the first few things that I would do after I started trying something new. Whereas Milady was the first thing where I attempted to be like, I'm going to go online with some intention to see what it's like to create an identity and to create an image and see what the relationship between those two things is. And also to see what happens when you try and distribute that identity a little bit. It just snowballed from there. What became Remilia was essentially a community of people that were doing similar experimental things. One of these was when they were having a conversation about what makes a good profile picture. Then what I was making was thrown into the mix as an example of a good profile picture.

Simon

Was that with work that you’d already been making?

Henry

Yeah, the first Milady was just me for a year or so it wasn't a distributed thing. I was making edits to the work, but eventually I realised that this is something that you can expand and distribute to a lot of different people. It was maybe not the earliest, but it was definitely at one of the peaks of NFT profile pictures becoming a common medium. So it was a good time to attempt a kind of top down version, where you already had a good PFP that was doing this distributed identity thing and then you fit it to the NFT profile picture thing.

Simon

So you were already messing with what a good profile picture meant as a single image?

Henry

Yeah, as like mimetic design and stuff like that. Obviously, that was with lifting from other places, editing and stuff like that.

Simon

What kind of other contexts would you be lifting from? Where was your research at that point?

Henry

Milady’s reference point is a figurine. I was looking at hundreds and hundreds of figurines and that was the one that stuck with me. There was this specific 90/45 degree view of that head. I think we've talked about this before, but the eyes being an anchor point for socialisation online, you don't really have much to lock onto when you're interacting with streams and streams of random profile pictures. So these exaggerated eyes on anime imagery give you an unfair advantage almost in that realm. I think we kind of just continued, or at least I continued to feel like there was something interesting so I was putting the idea of a project out there and saying: Could I make a system to arrange my interests into this new format? I think that was the most exciting and the most utopic thing about what Remilia was at the start. This question of whether we could all get together and actually make something interesting or something actually real happen.

Simon

Was that explicitly thinking about like social impact and scale in a way? Because you already had a form you were messing with, but what you're talking about is saying, we have this interesting thing but what if we pool all of our resources to try and make it scale to something that has impact.

Henry

Yeah for sure. You can run those kinds of experiments at a small scale and they’re still successful and interesting, but no one's really looking at them. Which I think is also a lot of the question about art the moment. I saw someone say that there is so much good art right now but it's not called art, or no one's thinking of it as art because it's in certain places that are lowbrow or too dopamine hungry.

Simon

Maybe that's always been true, right?

Henry

Yeah it’s probably always been true. I think it's a problem that you should always be trying to solve as an artist. I think you should always be trying to go and find that thing and pull it into the context that makes people actually appreciate it.

Simon

Which, in a way, is a form of cultural arbitrage. That’s what’s interesting about that role. I think that idea of something that has a spark, that is interesting and inserting it into a particular context to be looked at in a way that really resonates beyond the sum of its parts is the task. It’s interesting that you see this as similar to you messing around with ideas of what makes a good profile picture, with what is mechanically attractive in a certain context, and then how to deploy that within a particular space. For profile picture NFTs it's also a little unclear whether they’re art. I don’t mean that its unclear whether its a valuable thing culturally (many PFPs are both valuable and important cultural objects), its about whether its productive for them to be seen in the category of art. CryptoPunks claim to be art in a way and many people were saying that it was art, but again it just depends on what the claim is about – why does it help CryptoPunks to be framed as art?

Henry

I think a lot of the people who were making the judgement that Punks and stuff like that were art were not coming from a visual perspective. A lot of the people that were making that claim were making it based on how they existed on the blockchain or what they represented culturally and socially.

Simon

There’s an image of how they installed a screen with a Punk next to one of Warhol’s commissioned portraits in Miami a couple years ago and I think that is a meaningful and powerful proposition. It's deciding that the image of the network, which I think the Warhol commissioned portraits really are the first example of, should be deployed at scale. Because these are clients that make up the value network that literally produces the value of the Warhol project. It’s a kind of club and that's exactly how Punks behave. So I think the best proposition for them as art is that idea.

Henry

I also think that a lot of the thing about NFTs is is that they actually give an opportunity for value to accumulate in a singular place, even if its value that's collected from a lot of different places. I mean that's kind of true for Milady. That's kind of true for a lot of NFTs. It's also the reason that a lot of good art that's not called art is really hard to show, because it's an emergent TikTok trend or it's a style of Roblox avatar or something like that. You can't really capture that, like there has to be an artist or there has to be someone willing to capture that in a certain way so that someone can actually put it next to the Warhol and put it next to the Punk.

Simon

This also ties into what I think is really specific and interesting about the technical design of NFTs. It's about artworks or objects structurally as containers for the social value and the financial value that is given around a cultural community. So like the Warhol’s worth 10 million but that 10 million is produced by a tonne of people that support the fact that it's worth 10 million. This is what I think NFTs did using blockchains, they gave the possibility to have an image asset or whatever asset is linked to a token, and say, this is technically now possible to gather and keep and hold the financial value and the social value in one container. That's what's so awesome about it.

I knew about Punks and CryptoKitties earlier, but I think I really understood that financial container aspect vis-a-vis social only when NFTs really took off financially in 2021. It seemed to me this interesting thing about being able to isolate, show and gather in a kind of box, and that to me suggested the history of museums and what they do to cultural objects. I curated a show (Proof of Stake, Kunstverein Hamburg) that included a work by Timur Si-Qin which highlighted vitrines as tools that isolate and present. A vitrine isolates an object, it takes it out of its context, it tries to present it as floating without context, but it also claims its value and demonstrates a certain value by protecting it, by making it shinier, by making it unreachable, untouchable. Vitrines do that in museums and in shops. So thinking about about that isolation element and what that means to contain value and distribution. Maybe it's worth going from where you were working with Milady, which kind of exploded and where that lead you to what you're doing now because I think there's a link there.

Henry

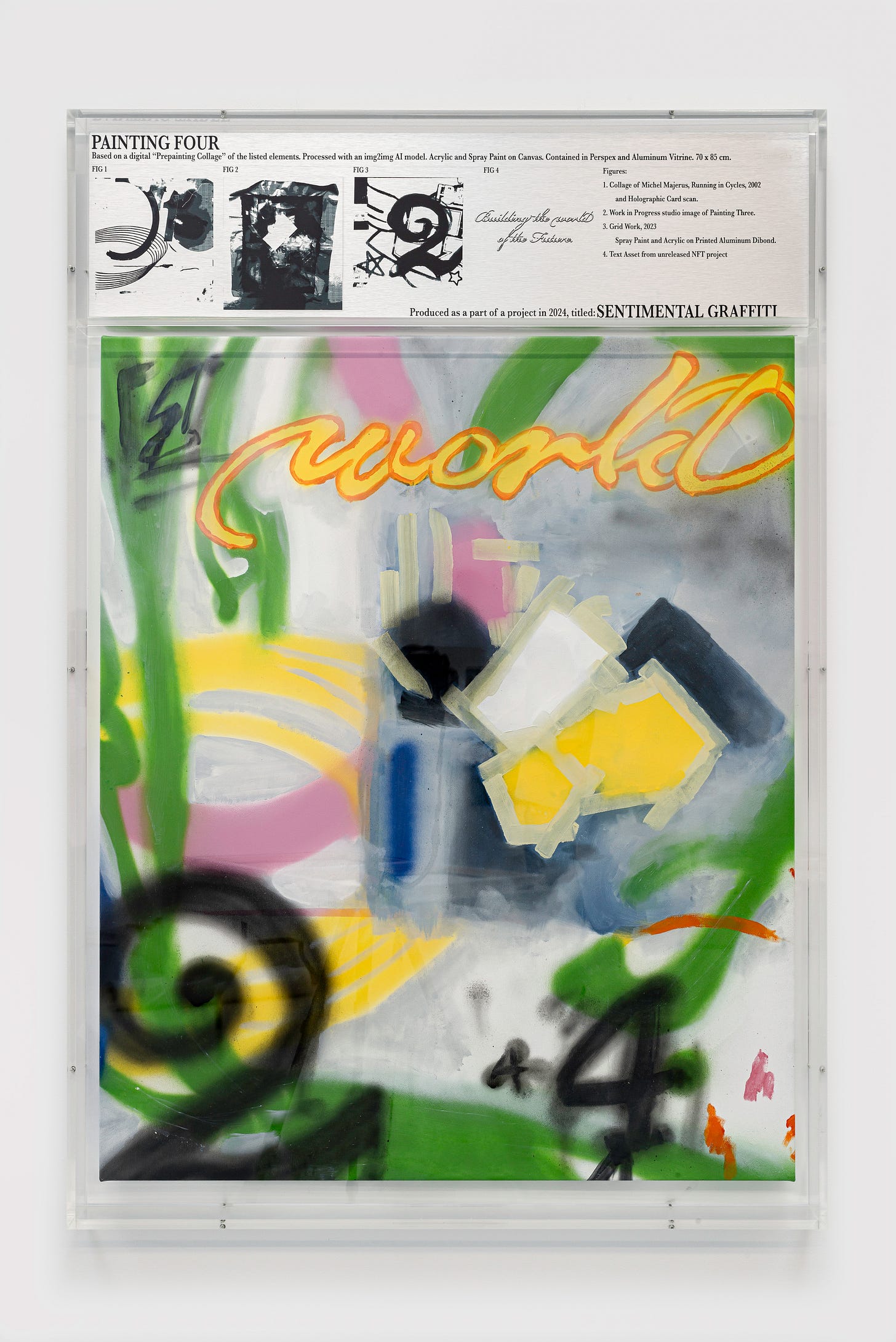

I'll summarise the project that I'm doing at the moment with Zien. It’s called Sentimental Graffiti. It’s an Expanded NFT project, so there’s a digital component, which is more or less a traditional NFT, but that is redeemable for a set of other physical items. Those physical items are at the highest tier, paintings, which are unique and then they can also be contained in a custom Perspex vitrine that has a header plate that decodes a lot of the references in the corresponding painting. Then there's also another tier that has a kind of coffee table style book. And there's also the ability to fit the vitrines with legs and convert them into this table piece.

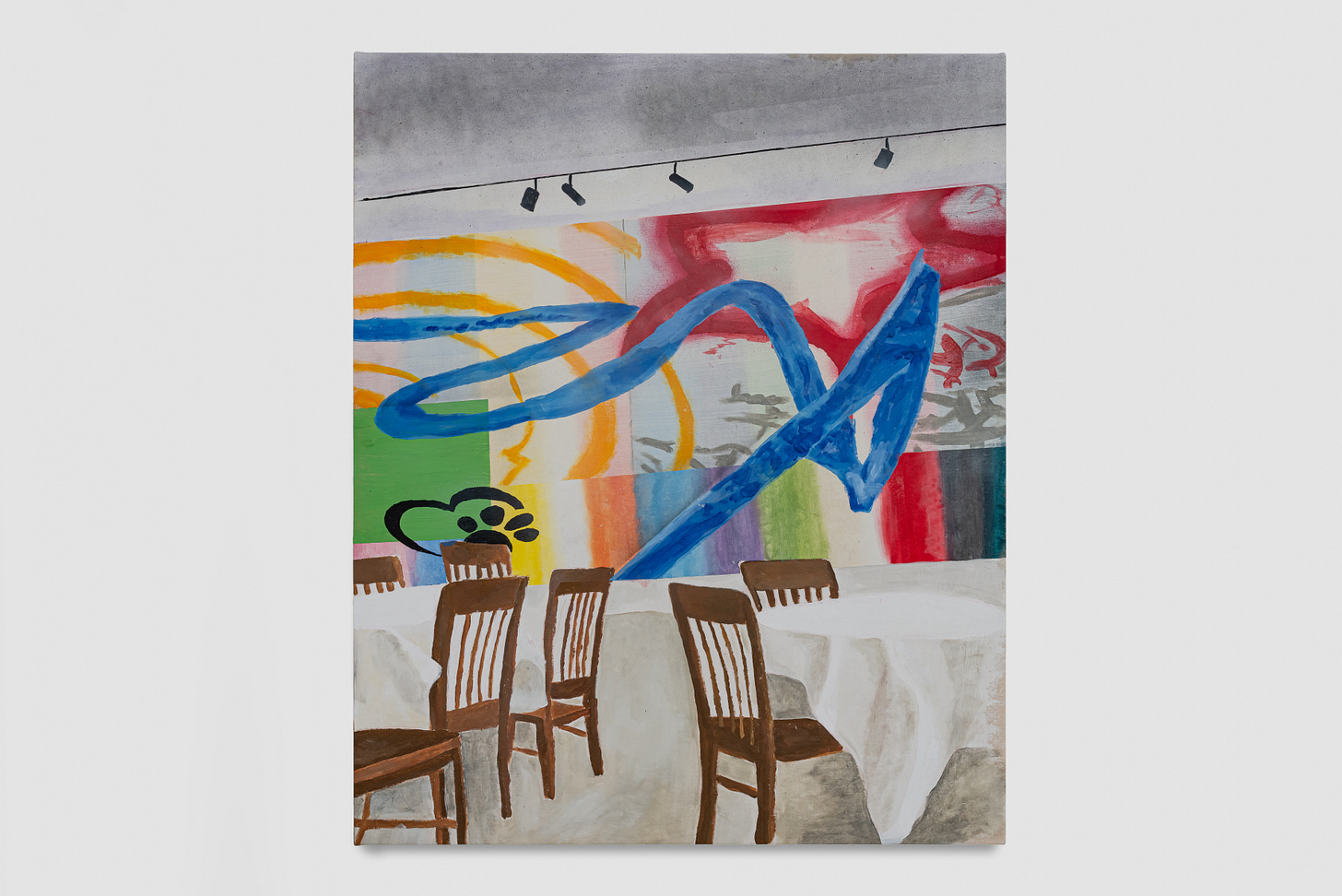

This is a progression of all the stuff that I was doing with Milady, as well as the general graphic work I was doing for Remilia and Bonkler. They were all about making these kinds of systems in which I could slot things that I was interested in and give them some sort of equivalency. That's kind of what I've wanted to do with these systems is take all the large amounts of imagery that I see or sift through and kind of make the suggestion that all the stuff that sticks in your head, or stands out, stands out for a reason and then to give it some equivalency. As an example, I'm going to reference the painting that's behind me, which is a dining room scene that comes from this installation image. It’s the only image that I can find of this installation from in the lobby of a hotel by Michel Majerus made in like 2001. I think it's the only image because he put up this cocaine molecule, this really kind of rave flyer looking image of a cocaine molecule, but he didn't tell the hotel what it was. So I think he had to uninstall it pretty quickly. But the table and chairs imagery is from there and then there's a wall install version of one of the paintings that I made that contains images from his other works but also images from my previous works. There's references to paintings that I made in like 30 seconds on a digital paint website and there's colour spectrums from the side of an anime CD. There's lots of stuff that’s taken from places that obviously do not have the same equivalency as a renowned and successful painter. But I like the idea of installing all those into the same place and then containing that in the vitrine to give it some elevation.

Simon

When you're deploying sets of profile picture NFTs there's almost an applied arts brief to making that product because you really want to do a particular thing.

Henry

That’s what I felt with making Milady. That it wasn’t just pure do whatever you want art, it did have to fit a few things, it had to fit into the archetype of a profile picture NFT and it had to feel like a community item. If it was too individualist then it wouldn't have succeeded.

Simon

Which is the difference maybe to the project that you're doing now. Maybe it's interesting to talk through another theme that I think about a lot when I'm making and also when I'm looking at other people's projects: complexity and depth. I think something that is true about my own work is that there are so many layers to things, some people can find it a little too complex. I've had feedback on my work that it can be layers of complexity that nobody really has time to enter. But there’s a big difference that I can see from designing a very particular outcome with a group of people to going into a situation where you're the sole author and you're designing a much more let's say networked system of meaning making as a project.

Henry

Complexity is like a sweet spot, right? You don't want to shut people out. But I think that's what I was talking about before around compression. You have to make sure that it can expand otherwise you didn't compress meaning you just destroyed meaning, more or less. As an experiment, I made a version of the Bonkler image which was like 150 by 200 pixels. I think there's nine asset slots, but as a compression exercise, I squished it down, so it was only three by three, nine pixels in total with each pixel corresponding to an asset slot. Technically, you're still going to explain it in the metadata, but it looses so much of its value, even though it's technically compressed and it's still technically expandable.

Simon

I think it's really interesting thinking about the design space for each project because it does have something to do with what you're trying to optimise for and also what you want out of the project. Maybe you can describe Bonkler for people that don't know it, because I think it is an interesting next step from something like designing for a profile picture NFT to this other more composable NFT.

Henry

Bonkler kind of broke out of that, it's not so much a profile picture but it looks like an NFT and technically it is an NFT and it is generated. But instead of being a profile picture of a singular character, it's more of a system with which to anthropomorphise a series of objects into a singular space. So Bonkler looks more or less like a pixel robot character and each slot is occupied by an object like a Donald Judd chair body or a background from a remake of this Flemish painters’ depiction of Prince Leopold in his gallery, but all the images are switched out with pixel art versions of my own paintings. I guess that was one of the first attempts at putting things on equivalency. So there's things that would never really be compared with each other, which is what I think is interesting about NFTs, the ability to use that generative software to find linkages between things that you would never normally or, not that you would never find them, but you'd have a tough time combining.

Simon

It’s kind of a consistent thread for all three projects. You're combining and linking and putting out jumbles of stuff that aim to connect with a particular type of person – somebody that can recognise elements in the collage and relate to them.

Henry

Sometimes that person is yourself as the artist, but sometimes there's definitely stuff that's in Milady and stuff that’s in Bonkler that isn't necessarily because I wanted it in there. But it was because it was an interesting next step from something that I did put in, or it was interesting to say that if you liked this then you might also like to go down this path. I think that’s just an effect of the network as a whole. Like that's how people's media consumption works at the moment. Most of the time, if you ask someone how they found a new musician or a new artist, it's often like, well, I was looking at this, and then I looked at this, and then this and then this and this. I chose a series of forks in the path until I got to where I'm at. That's kind of what I wanted to do with the pre-painting process for these images, to add some of that random choice to it or add some of those computer controlled elements to it.

Simon

There was something that came up at the beginning of art and web2 in exhibition making. I remember the first show that did a good job of framing post-internet art was this show called Free curated by Lauren Cornell at the New Museum. It was all about this notion that image search was making this sort of equivalency of images and what is it when artists can do whatever they want with something and then spit it out again? As web2 dragged on and social media platforms turned into something people started to realise that there was all this labour being done that was being syphoned off in terms of value for these five companies. This is when the idea of web3 and NFTs as a way for the users who are creating the value to capture some of that emerged and this is where something like Remilia and the whole thing around successful projects like Milady really make sense as a new iteration of social. It's also interesting that you as a key part of that are still thinking about what is a space where I can do a kind of a collage that also fits into something meaningful socially.

Henry

I feel like there was a bunch of artworks that attempted to capture things like this but they never really felt meaningful in that way or they felt like they were making fun of the thing that they were trying to capture. That is definitely part of the reason why web3 stuff came about, but I think it also presented new opportunities for things that previously were unable to be captured.

Simon

That’s a really interesting distinction. There are these people that came from web2 adjacent art, I'm thinking of artists like Brad Troemel, who got sick of the role of the artist in that web2 mode and found it impossible to monetise within the traditional art world, that kind of pre-web3 transition into this sort of Patreon creator economy model where you have a subscription to get his shit posts and memes.

Henry

That is kind of like the bridging point between the two. The thing that I said about making fun of it. There's definitely a distinction between artists that were interested in the internet as this kind of shock factor or as this kind of look at how weird it is on the internet. But I think what's happened is, as it became more and more a part of people's lives, or just younger artists have spent more of their formative time on the internet, it's less so about look how strange this thing is and more about this is where I am and this is the context in which I think that new things are happening. I think they were like simultaneous cultural changes happening.

Simon

One of the really central reference points of Sentimental Graffiti is the painting of Michel Majurus. His paintings bring in contemporary design from the internet, from the emergent 3D graphics world and from contemporary sneaker design of the late 90s and early 2000s. It’s exactly about not being like this shoe looks fucking crazy, but it's like, this is now. There’s textual references in his work too, because he often played with language to augment the material. I remember I first saw Majerus’ work on the cover of Artforum when he died, a reproduction of “what looks good today may not look good tomorrow”. That phrase alone is really interesting.

Henry

He was also using Photoshop and he was using projectors to paint by numbers essentially. He also admitted to playing the role of a painter. Do you know what I mean? He was a painter of course, but he was also performing it. In the current context, I think so many people are finding something they want to be and kind of performing it, which I think is often a valid path to it. But there's something interesting about the intentionality of a very self-conscious thing that he would emulate. To become a painter by emulating a painter.

Simon

There was a very specific cultural and historical origin in the place he started painting. Also other artists that you've mentioned that you're interested in, like Martin Kippenberger, who was, of course, maybe the icon of that type of performative artists behaviour in the 1980s and 90s. Its a history thats very visible in certain communities in Germany. That's part of the tradition that Majerus was working in, I guess.

Henry

It also gave him a certain amount of freedom and I think that freedom is what makes the work still feel fresh now. When he was doing the more abstract works, that freedom to be able to just throw some paint onto the canvas and there’s this kind of sense that it didn't matter that much, because he was performing as an abstract painter.

Simon

There's a light touch that’s important to it. It's again something I recognise from that cannon because I think Kippenbeger was like that. I went to art school in Frankfurt and one of the people that seemed very visible at the time in some people's imaginary was Micheal Krebber – especially in his class of course when he taught there. And Krebber’s work also has the light touch to it. His whole project is famously “unfinished too soon”.

Henry

The other artist that I reference in a bunch of the paintings is Albert Oehlen, who is also part of that group. I've seen him be like questioned about a reference, someone will be like, you always use this specific image of this guy with glasses and a moustache or whatever. And he basically just says, I never actually thought about it, I just happened upon that image and I liked reproducing it and I've done it 20 times, but I've never really thought about it. There's also that kind of lightness.

Simon

There’s an internet-ness to that also. You make a collage and put it out as a meme. You don't think about it all that much and then it gains value by being moved around in particular circles.

Henry

Right, it accrues its cultural value after you’ve thrown it out, which I think happens in normal art too.

Henry Sprite’s Sentimental Graffiti is dropping on Tuesday 11th June 14:00 UTC.